Pieter Stockmans volgt het mondiale optreden van de Europese Unie, het Europese vluchtelingenbeleid, de evoluties in Midden-Europa en de regio ten oosten van de EU.

Poor Poles count on right-wing politics for social protection

Common families increase the power of populist, nationalist anti-immigration parties in Europe. This is clear in the southeast of Poland, where undeclared work and emigration are survival mechanisms to escape unemployment, low wages and insecure working conditions. Pieter Stockmans travelled through “Poland B” for two weeks.

‘Our son is sick and we can use PiS’ child support very well.’

© Pieter Stockmans

Feet are stamping feet, the dance floor is swirling, vodka is poured freely. City kids are dancing the Mazurka, a Polish folk dance from the countryside, at the annual traditional music festival in Warsaw. The economic growth went as fast as the dancing couples spin around their own axes. Poland is sometimes called the economic miracle.

In 1990, the country was worst off of all Eastern European countries; twenty years later, during the crisis year of 2009, Poland was the only European country whose economy continued to grow.

But the benefits were not reaped equally everywhere in Poland. ‘The growth of the income per capita for the bottom 40%, lags behind the growth for the whole population’, the World Bank writes. Professor of Economics Marek Góra from the Warsaw School of Economics confirms: ‘The increasing level of wealth and the employment are concentrated in the metropoles. Rural areas are a different story. If you travel from the capital Warsaw to Podkarpackie (Subcarpathia, the southeast of Poland), you arrive in a different world.’

Podkarpackie

Podkarpackie

The hypermodern infrastructure reflects the economic boom in the capital. The high-speed train from Warsaw even has internet connection. The old, noisy, slow trains that still run in Podkarpackie would be an anachronism in Warsaw.

According to Social Diagnosis 2013, an official study of the Polish economy, Podkarpackie has the lowest average monthly wage, which is 250 Euros. For Warsaw, this is 400 Euros. The majority of the people in Podkarpackie live on the countryside. Poverty is most common and deepest in this area. At the same time it is the most religious province. Here, the Catholic nationalist party PiS (“Law and Justice”) obtained up to 60% of the votes.

The eastern provinces are scornfully called “Poland B”, a name which PiS adopted as a badge of pride. This party, known in Belgium for undermining the rule of law and for their conservative, right-wing positions, presents itself in Poland as an advocate of the “precariat”, usually the electorate of left-wing parties. The precariat is a relatively large group of Poles living in precarious circumstances.

Baligród is a village on the edge of the Carpathian Mountains. At the public company for forestry Grażyna stands with her grandson. ‘My son does all kinds of chores there, but they are not giving him a fixed contract. My daughter-in-law takes care of the elderly in the village’, she says. When I ask her if they work undeclared, Grażyna is surprised. ‘Would you pay taxes on those crumbs? Officially, they are unemployed.’

Grazyna: ‘A man in the village died in an accident at a construction site. He was not insured because he was working undeclared. His family was left behind empty-handed.’

© Pieter Stockmans

The closure of public companies in the agricultural sector after the fall of communism and, more recently, the closure of factories due to the transition to a service economy, led to structural unemployment in this region. Investment in tourism would create opportunities, but this hasn’t happened yet on a meaningful scale. Undeclared work and emigration are often not choices, but survival mechanisms.

‘When you are drowning, you would even hold on to a sharp knife’, Grażyna sneers. She refers to the success of PiS in Podkarpackie. Grażyna still lives in a wooden house, but last year she saw a stone house arise at her neighbour’s. Paid with money they earned through seasonal employment in Italy. The daughters of Grażyna’s sister on the other hand, work in the United Kingdom.

Since 2004, the year of Poland’s accession to the European Union, many Poles, who up until then were unemployed and worked in the shadow economy, emigrated. The Poles who already worked abroad before 2004, often undeclared, could regularise their work situation. Many of them kept on working undeclared in addition to their regularised job, to be able to send more money back to Poland. The Polish Central Bank estimates the value of the money sent back to Poland by emigrants as 1.2% of the Polish GNP.

‘They steal our jobs’

Between the wooden houses and clean grass lawns, the picturesque dirt roads twisting through the village, and the calming sound of the mountain river, the grey communist housing block is an abominable sight.

Several cars with British license plates are in the car park by the building. Joanna, a slender girl, is carrying her groceries inside. She is studying to become a kindergarten teacher. To pay the rent, she does small jobs in stores. ‘Most women in this housing block have already gone abroad, they came back with modern iPhones’, she says timidly. ‘The men work in construction, undeclared. A friend of mine died in a work accident. Because he did not have any insurance, his family was left behind empty-handed.’

That night I stay at Dorota’s B&B. Dorota rents out rooms in her house behind the dilapidated Orthodox Church. Friend of the family Wojtek has been drinking self brewed vodka since five o’clock in the afternoon. The empty dance floor reminds of better times. ‘We had to close everything down’, Dorota says. ‘Because of the high taxes we were only making losses. The liberal party never looked after Podkarpackie because they cannot get any votes here anyway. Almost everyone votes for PiS, we follow the advice of the priest in the church.’

‘Poles expect everything from emigration, but are against immigration. Where is the logic in that?’

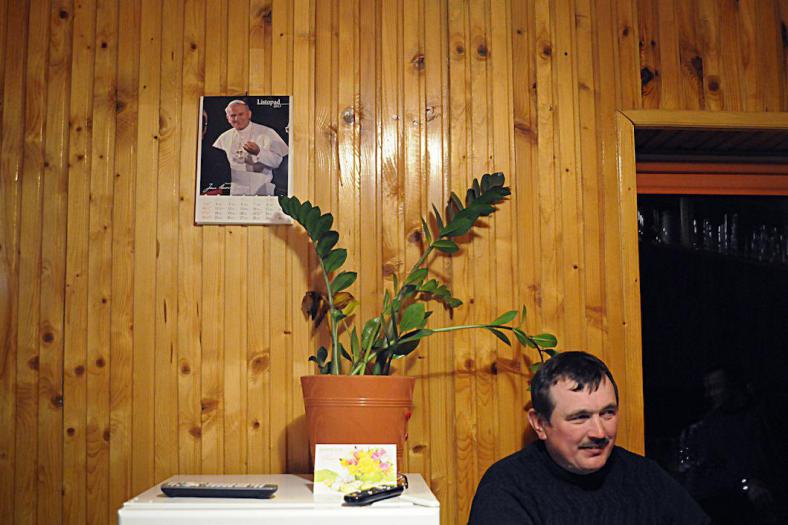

Wojtek does not. Sitting on a stool under the portrait of the Polish Pope John Paul II, he laughs at Dorota and her husband: ‘Your vote will only make things worse.’ With every glass of vodka, he becomes more sharp-witted. ‘Poles expect everything from emigration, but are against immigration. Where is the logic in that?’

What Wojtek is referring to: PiS is angry about British Prime Minister David Cameron’s negative comments about the 580,000 Poles in the United Kingdom (out of 64 millions of Britons), but is spreading similar stereotypes about the small group of 7600 refugees (out of 38 millions of Poles) the previous government agreed to take in.

Dorota’s husband objects: ‘They steal our jobs and we are condemned to undeclared work and emigration’, he mumbles. He is repeating the discourse of the Polish President Andrzej Duda (PiS). The Polish economy is still trying to cacth up with the rich Western countries and to increase the standard of living of Polish youngsters. This would allow them to contribute to the Polish economy instead of foreign economies.

Wojtek: ‘Your vote for PiS will only make things worse.’

© Pieter Stockmans

It is not certain that the Polish migrant workers in the United Kingdom will be able to stay there, in case of a no vote in the British referendum on EU membership on June 23. Entire communities in south-eastern Poland would lose their income and join the local shadow economy.

Poland has one of the highest negative migration balances in the world. Today, 2.5 million Poles live abroad, although the increase becomes smaller every year. More than half of them live and work in the United Kingdom and Germany.

The highest economic growth in Central Europe, and yet the highest emigration rate and support for populist parties? ‘Inequality between wages or standards of living in Poland and those in Western Europe is still the driving force behind emigration from Poland’, says professor Marek Góra. ‘The past twenty years we went from 43% to 68% of the European GNP per capita, but our expectations grow faster than the economy’s capacity to meet them. Populist parties like PiS do not explain that, they exploit it.’

500+

The next morning, the bus drives through the morning dew above the fields of Podkarpackie. In the village of Blizne, Magdalena gets on the bus. She is on her way to Rzeszów, the capital of Podkarpackie, where she studies to be a beautician. Like Joanna, she makes a submissive impression, as if she is ashamed of the questions I ask her. ‘To find a permanent job here, connections are more important than competence. I studied management, but I have been unemployed for over a year after countless applications.’ Youth unemployment in Podkarpackie rises up to 40%.

‘If your monthly wage is 300 Euros, a monthly child benefit of 110 Euros makes a large difference in the family budget.’

Magdalena married young, but they cannot start having children yet. ‘We still live with my parents. We try to save money in all possible ways to buy a house. My husband works 15 hours per day in a bar. I work as a nanny, undeclared, of course. Last year I joined my mother for a month to pick grapes in Luxembourg. For the amount I earned there in one month, I would have work four months in Poland. My dream is to start my own beauty salon, but the taxes for entrepreneurs are so high.’

Magdalena voted for PiS. She immediately mentions the 500+ programme, the main proposal of the party. Young, vulnerable families receive a monthly child benefit of 500 złoty (110 Euros) per child. ‘If your monthly wage is 300 Euros, that makes a large difference in the family budget’, Magdalena says. ‘It allows us to start having children.’ And that is the government’s objective: Poland has an exceptionally low fertility rate.

Lublin

Radio producer Alina Pospischil works under junk contracts

© Pieter Stockmans

Alina Pospischil shows me all the places in Lublin that breathe a progressive atmosphere: modern coffee bars, a vegan restaurant, the annual jazz festival that, also this year, attracts full venues. As a journalist for the Culture Department of Radio Lublin, she has her hands full. Every day something is happening in this city. In summer, all the corners of the old medieval city come to life with Polish folk music and open-air theatre.

But the economy sputters. Alina, too, deals with insecurity. ‘At Radio Lublin, a public broadcaster, I work under so-called junk contracts. Those are temporary contracts which are renewed each time’, she says over a plate of pierogi. She is not protected against arbitrary dismissal, illness or work accidents, and she is not building up pension rights.

‘If this precarious form of employment persists, we will face major problems. When this generation without retirement pay becomes old, society will pay a large price’, professor of Economics Marek Góra warns. ‘A grey, parallel economy of Poles with less rights than other Poles is already growing.’

Out of all European member states, Poland has the highest number of employees with temporary “junk” contracts for de facto permanent jobs. 44% of the youngsters work under this type of contract. ‘With temporary contracts, employers try to evade high administrative costs, taxes and social contributions’, professor Góra says. ‘The existence of these contracts encourages companies to employ people. This explains the low unemployment in Poland. Employees from their side, have to pay less taxes on their wages, and are thus able to save more money in a brief period of time.’

But Alina wants security: the coming months, she plans to buy a flat and next year she will marry her boyfriend. With temporary contracts, it is difficult to get a loan from the bank. ‘A colleague of mine had a motorcycle accident. The surgery cost 16,000 Euros. With a permanent contract, he would have been insured and he would not be paying back that surgery for the rest of his life, but his boss refused.’

The hard-working Pole

This is, of course, a concern for Marian Król, chairman of the local department of Solidarność, the world-famous labour union that caused the fall of the communist Polish government through massive strikes in 1989.

‘The other side of the coin of the Polish economic miracle: flexibility for foreign companies and insecurity for hard-working Polish families. The PiS government will tackle this problem’, he says at the monument of Lublin July, a giant cross and the statue of a worker breaking his chains.

In July 1980, Król was one of the leaders of the strikes in several big factories in Lublin. Those strikes led to the formation of the independent labour union Solidarność in Gdansk, where history was made nine years later.

‘Is that journalist left-wing or right-wing?’, my contact at Solidarność asked. He seemed to suggest that all Western European journalists are by definition “left-wing” and thus against Poland. Krysztof Bogusz is a worker at a chocolate factory. He wears a little cross around his neck. ‘It does not surprise me that Western Europe is against PiS’, he says. ‘The Polish worker is weak against the big Western European companies and PiS wants to change that. The liberals led us to believe that foreign investments would solve all our problems.’

His wage is too low to pay off loans, so he does several jobs in his spare time. When I ask him how he feels about that, only a deep sigh follows. In short: this is the tension between economic growth and human development which Pope John Paul II discusses in his encyclicals Laborem Exercens (1981) and Sollicitudo Rei Socialis (1987).

Król, in whose office hangs a portrait of the Polish pope, is very clear: ‘We advised our members to vote for the party defending workers. Today that is PiS. Moreover, we reached a preliminary agreement with President Duda (PiS): he would adopt our proposals and our members would vote for him. For now they are keeping their promises, so we have no reason to strike.’

According to Jarosław Kaczyński, president of PiS, the subordination of Poland B was a secret conspiracy. The Polish state had to be purified.

Tomek, a deeply religious father who is playing in the park with his son, speaks softly, like a priest: ‘Working eight hours per day is not enough to afford a dignified life here. The Catholic Church is our strength. God will protect us and the PiS is standing up for us.’

During the transitional years, widespread fear and insecurity led to distrust against the elite in the big cities. Three populist movements took advantage of this radicalisation: Polish Self-Defence, a farmers’ movement that emphasized the unequal growth; the League of Polish Families, Catholic nationalists who wanted to protect Poland against atheist communists and secular liberals; and PiS, founded by the Kaczyński-brothers and arisen from the radical illiberal wing of Solidarność. They were against the division of power between communists and liberals, brought about by the moderate liberal wing led by Lech Wałęsa, who became president. According to Kaczyński, the subordination of Poland B was part of a secret conspiracy. The Polish state had to be purified.

Tomek: ‘The Catholic Church is our strength. God will protect us and PiS is standing up for us.’

© Pieter Stockmans

Poland B versus Poland A

In a traumatised country that was wiped off the map by secret deals between superpowers multiple times, such a story of resistance against economic and political exclusion and moral decline resonates. From now on, it was Poland B versus Poland A: the authentic Polish people against the foreign elites in the developed cities.

In 2006, the three populist parties even briefly formed the government. The coalition collapsed due to internal disputes and barely managed to achieve anything. The liberal party came to power and stayed for the following eight years. If the economic crisis had struck Poland as well, that might have gone differently.

Still, something was rotten beneath the surface. From 2004 until 2008, unemployment decreased from 19% to a low 7%, but rose again to 10% in 2010. From 2008 to 2013, youth unemployment rose from 17% to 27%, above the European average. The economic growth obscured the high number of junk contracts, which led to insecurity about the future. The cherry on the cake was the refugee crisis, which helped PiS capitalize on a mix of political-economic dissatisfaction and moral identity issues.

Ten years after their brief time government, they are given a second chance. And now they get to do it all alone. For the first time since the fall of communism, one party obtained an absolute majority in parliament. PiS now has president, government and parliament.

The Visegrád Group, a coalition between Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, is now run by four populist governments.

The Polish elections had European consequences. The Visegrád Group, a coalition between Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic and Slovakia, is now run by four populist governments and forms a powerful opposition to the Europe of Germany and France. This was already felt in the European refugee policy.

In her inauguration speech, Prime Minister Beata Szydło (PiS) lashed out against the liberal system and spoke up for the hard-working Pole. She wants to drive up social support, develop rural areas, abolish junk contracts, tackle youth unemployment. Ambitious policies that could push back undeclared work in Poland, but child support for vulnerable families will cost 3.5 billion Euros in 2016 alone.

‘Their very expensive, populist measures will not make a structural difference’, employment mediator Aleksandra Obara giggles. Many residents of Lublin pass by her office: low-skilled and long-term unemployed people nobody wants to hire anymore. ‘They tell me that they earn some extra money by doing undeclared work in construction. Also highly educated people face difficulties. The city has four universities and more than 40% of its inhabitants is below 35 years old. Thus, many youngsters enter the labour market each year. They work hard for a degree and then I offer them a low-paying job as a cleaner or warehouse assistant.’

‘Our son is sick and we can use PiS’ child support very well.’

© Pieter Stockmans

Lubelskie

One street, 200 houses. That is Strachosław, a sleepy village in the vast plains of Lubelskie province. Many inhabitants no longer enjoy the green fields, the white cherry blossoms, the sheds full of piled up wood and the stork’s nests. They have left for the city or abroad.

Michał and Paulina are one of the few young couples still living there, with Paulina’s parents because they have not yet been able to build any financial stability. Paulina works as a nurse in a private clinic, with temporary contracts.

For years, Michał took on all sorts of small jobs, sometimes without a contract. ‘If you want to work, you will find work’, Michał says. ‘Helping out in a printing company, doing dishes at a restaurant, disassembling mobile phone masts. Now I am a warehouse assistant. To get a loan from the bank, however, I have to find a job with a higher wage. That is why we are moving to Lublin.’

Youth who become focussed on the lack of job security and the temporary employment in low-skilled and low-paying jobs, do not care much about PiS’ extreme image, but pin their hopes on their social policies. ‘The next four years, we will see what PiS is worth, but meanwhile, their child support is worth a lot to us. Yes, I voted for PiS’, Michał laughs. The liberal government made them pay more taxes, while the anti-liberal government gives them money.

A few houses down the line, Szczepan is concluding his working day at the local garage. We sit down on a bench by a life-size statue of Mother Mary. ‘I work here with temporary contracts, but that is not a problem for me because I am insured as a farmer’, he says. Next to the garage, his mother runs a grocery store in what used to be his parental home.

Strachoslaw, a sleepy village in the vast plains of Lubelskie province.

© Pieter Stockmans

‘We used to have three stores, but we had to close them down, the taxes were too high. That is why many people here work undeclared. The palette company employs twenty people: five of them have a fixed contract, the others work undeclared. They are registered as unemployed and receive benefits, and at the same time, they earn money undeclared.’

Szczepan laughs at my questions: ‘Everybody knows that here. It is normal in our situation, isn’t it?’ The European Commission and the Polish Ministry of Economy estimate the share of the shadow economy in Poland to be about 20%, comparable to most Southern and Eastern European countries. In some rural areas, this percentage rises up to 50%. In most Northern and Western European countries it amounts to 10 to 15%. Exceptions: Belgium with 16% and Ireland with 30%.

Golden Hand

The closer you get to the Ukrainian border, the more wooden houses you see. In Dubienka, a village within a stone’s throw from the border, the name of the communist farmers’ cooperative that closed 27 years ago can still be read on an arch above the entrance.

Five years ago, I celebrated Christmas in this village with Aneta, the aunt of the Polish singer Olga Kozieł. Five years later, I find them in the same wooden house with only a kitchen and two rooms. Aneta and her seven children belong to the 1% of Polish households living below the deep poverty line. ‘You can see for yourself what has changed in the past five years’, she grins. ‘The children still sleep on mattresses on the living room floor. Only the husband has changed. My ex-husband left for England and does no longer bother about his children.’

Aneta: ‘Later I will depend on my children. In my whole life, I have only worked eight years legally. My pension will be too low.’

© Pieter Stockmans

Jarek is Aneta’s new partner. We gave him a ride after work. ‘I am a worker for a company that drills for shale gas’, Jarek says. ‘If I had the time, I would have an undeclared sideline job too. But I have to work six days a week from early in the morning until late in the evening. I sleep at the workplace and I only come home for the weekend.’

Legally, Aneta has only worked eight years in her whole life. She is concerned because her retirement pay will be too low if she does not find a job. She did work a lot, undeclared. In Dubienka she is known as “the golden hand”. ‘I did chores everywhere: from painting walls to fixing electronics, you name it. But the men in the village became angry with me for taking their jobs’, she laughs.

Next month, Jarek will explore a different option: he is going to work in construction in London. Maybe Aneta will follow with the children, but she doesn’t hold much hope. Also PiS’ promises do not arouse much enthusiasm. ‘I did not vote, certainly not for PiS. I cannot stand them, but I have to admit their child support helps out a lot.’

When we say good-bye, four storks fly over the house, a sign of good luck. How will I find this family in another five years from now? Olga feels sad when she sees her seven nephews and nieces in poverty. In Lublin, her nieces from her father’s side are visiting. Their father travels around the world as a banker. They demonstrate their skills as mandolin players and gymnasts. Between these two extremes within Olga’s family there are many levels of economic insecurity.

Olga goes her own way as a young artist-entrepreneur, seeking a new identity for 21st century Poland. Open to the world, yet keeping its own identity. The cosmopolitan and tolerant Poland of yesterday, the Poland of tomorrow?

This report was realised with the help of Polish journalist Alina Pospischil.

Translation by Ayden Van Steenlandt.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2793 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Podkarpackie

Podkarpackie

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International