Testimony of a Syrian metalhead with a camera and a stick

Syrian, alawite, opposition, war photographer, war wounded. Artino is all, and more. This is his story how he lived the Syrian revolution till now.

I am a computer salesman, a brother, a photographer, a witness, a son, a humanitarian,a Muslim, a traitor, a victim, a bodybuilder, an atheist, a hero, a refugee, a Syrian. I have been called all of these things and this is my story. My name is Artino and I was born in Damascus in 1983.

My mother was Circassian, and a Sunni. My father was an Alawite.

Both my parents were from Golan - the mountainous area in the south of Syria that has been occupied by Israel since 1967. My mother was Circassian, and a Sunni. My father was an Alawite. Because my mother died while giving birth to me, her third son, I was brought up by my maternal uncle and his wife in the Barza area of Damascus.

My biological father was an intelligence officer in the Syrian Air Force, part of the machinery of the Mukhabarat no less.

After my mother died he married again and started a new family. I had a pretty good childhood, my aunt and uncle treated me as if I was their own child but it was lonely as I didn’t have my brothers around me.

Because of my injury, I had to lay down and take pictures. Another photographer started taking pics of me.

© Artino (Sept 2013)

I studied English translation at the open college section at Damascus University. With classes only on Fridays and Saturdays, I worked the rest of the week first as a salesman at Toshiba and in my last year I was recruited by Apple. They trained me up as a supervisor and soon I was responsible for selling Apple products all over Syria.

But everything changed with the Arab Spring.

The early beginning

I joined the protest movement right at the start. We had been watching what was happening in Tunisia and Egypt, and I turned to my best friend and whispering to her: ‘Do you think we could do this here?’

The Syrian authorities have always been notoriously tough. They bought in a new law which stated that it was illegal if three or more people gathered in one place.

Then we started to hear rumours of Daraa: kids had been painting slogans, the kids had been arrested, one kid had been killed. After this we started to mobilise.

We created closed groups on Facebook to plan our strategy. We wanted to prove that our movement was not only peaceful but also well supported and well organised. With gathering classed as illegal it was agreed the marches would start from the mosques after Friday prayers and being the weekend we were free to attend. My Christian or non-religious friends would join us outside and women would come after their prayers.

We really thought that our peaceful protest would beat him. There were so many of us.

One week we decided instead of marching we would all wear white and walk around central Damascus in ones and twos. There were loads of us, and whenever we passed each other dressed from head to toe in white we would give them a shy smile. The secret police didn’t know whether to arrest us or ignore us.

We printed anti-government slogans on ticker tape and then on ping pong balls and distributed them close to the Bashar al Assad’s compound.

We really thought that our peaceful protest would beat him. There were so many of us. When the older generation joined the movement we felt invincible.

My little friend in Lebanon. It’s a very emotional pic because of our friendship, the flag…

© Artino (Sept 2015)

After a few weeks the police began to shoot to kill, an order had come through. But instead it only made us stronger. Emotions were running high and now funerals became the catalyst for the protests.

In deciding to be a part of the revolution I lost many friends. I am an Alawite, the same as the Al Assad family and much of the military establishment, but I hated the corruption that was so rife in all parts of Syria. I wanted to live in a country where everyone could be seen as equal. I had grown up seeing how people used and abused their influence. Our campus was very divided and many of my friends were Alawis too. I heard them discussing the protests and they were astounded when I started defending the activists.They told me I was betraying my people.

First arrest

Two weeks into the the uprising I was arrested. A government agent filmed me carrying the coffin of one of the early victims. They picked me up as I passed through a checkpoint on the way to Damascus a few days later. I was taken to the notorious prison of the Mukhabarat, the Syrian secret police. The officers couldn’t believe someone like me had joined the opposition. I was placed in solitary confinement, blindfolded and strapped to a chair.

‘Why are you doing this? Why do you betray us when Dr Bashar gave you everything?’

Every time a soldier would enter my cell he would kick or hit me. I was moved several times. I think they took me down to the basement where my captors would start laying into me. They’d shout and swear at me, “Why are you doing this? Why do you betray us when Dr Bashar gave you everything? You come from a good family and have an education Why have you joined the terrorists?”

There was one particular guard, he must have been a big guy because I could feel his huge hands when he smashed me with his fists. One day I’d had enough so I shouted at him, “What have I done? Uncuff me, take off this mask! Why won’t you show me your face, are you a coward? Why can’t we talk man to man?” He went crazy and picked up the chair, and threw my full 70kg weight against the wall. After that the guards would spit on my face each time they entered the cell.

I was also subjected to the infamous flying carpet; a prisoner is strapped down to a hinged board and the ends are brought together. The aim is to bend the spine and inflict maximum pain.

The prison experience still haunts me. When I came out, I felt so unclean that I would spend hours in the shower. Later you started hearing rumours of new interrogation methods being used: sexual abuse and torture using electric rods.

Two of my good friends died at the hands of these butchers, Mohammed Zereek, who was a student, and also a dentist called Ayham Ghazoul. These were the rising stars for the next generation, brave enough to speak out against injustice.

The fate of many of the revolutionaries arrested in those early months is still unknown. We have no idea whether they are still being detained, languishing in a prison somewhere or if they have been killed.

Freed by roots

My real name is Mohammed Abdullah, which sounds like a regular Sunni name, but my father’s birthplace, Ain Fiet, a well recognised Alawite village is printed in my Syrian ID. This has been alternately a blessing and a curse.

My father was, as I told before, a military man and because of his connections within establishment circles, he was able to secure my release. He had to pay about $1,200.

After I was freed I had to swear that I wouldn’t rejoin the protests. I couldn’t keep that promise.

People say: ‘live in the moment’. Syrians say: ‘live every moment’. The man was taking a last look at his bombed house and began his search for a new home.

© Artino (Jan 2013)

I went out to the demonstrations every Friday. I began to use my Alawite background to further the cause. Towards the end of 2011 I joined the smuggling operations to Homs and Hama. At the checkpoints I would flash my identity card at the soldiers. They wouldn’t dare to search my bags which were full of medicines destined for those injured in the demos.

My mother dressed me in the traditional clothes women of Ghouta sometimes wear, the ‘khemar’, layers of black cotton.

In 2012 I found out that the authorities were after me. I had broken the terms of my release. I was briefly arrested after I had been seen at a huge demo at one of the big malls in Damascus. So in May 2012 in July I escaped to Ghouta, a rural area to the east of the city where my adopted parents had a house.

Syrian soldiers were searching the area. Anyone they saw as a ‘rebel’ or ‘traitor’ would be arrested or shot. So my mother dressed me in the traditional clothes women of Ghouta sometimes wear. The ‘khemar’ are layers of black cotton that cover the whole body including the face and hands.

Whenever we heard government forces were close-by I would be told to go and sit with the women of the neighborhood. With time on my hands I began helping with the internally displaced people (IDP) who had escaped from other towns in the area.

Lebanon I

But there is only so much one can take of this constant hiding so in September I decided to go to Lebanon. Before the war we moved freely between the two countries, it takes an hour and a half to travel from Damascus to Beirut by car. Now the only way through was via the smuggling network, which is always risky. You don’t know how much you can trust the smugglers or whether they will betray you to the government forces. You are moved from safe house to safe house, and passed from group to group, sometimes it’s the Free Syrian Army (FSA) and sometimes individuals who could be best described as gunrunners or bandits. It is a terrifying process, your heart is constantly in your mouth, you jump at any noise. I asked around for the most reliable contact and in this case I paid the smuggler well so the journey took just a single day.

I left home without telling my family. It was for their own safety. If the authorities came knocking at their door I wanted to be sure they would have nothing to say.

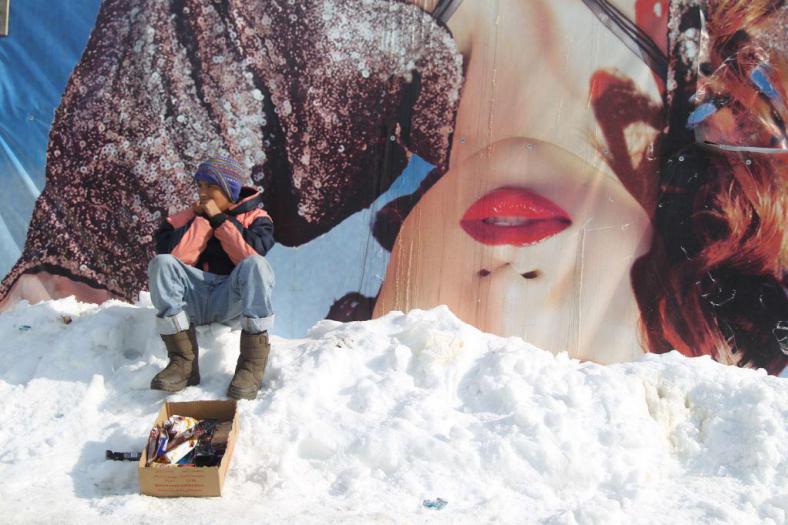

Refugee Camp in Lebanon. Biscuits selling boy / reality check in front of ad world.

© Artino (Jan 2015)

All I could think about was Syria. Every day hundreds of people were arriving in the camps. Who was left back home to help those most in need?

When I rang my mother from Lebanon, she was confused by the foreign dial code, she thought I had just gone to Damascus or somewhere. I mumbled my apologies and she started to cry. She kept saying over and over, “God bless you, God bless you my son. I hope to see you again.” I could hardly control myself.

We aren’t able to work in Lebanon so like many Syrians I volunteered with the refugees in the Bekaa Valley: organizing children’s activities and delivering aid. But I was restless. All I could think about was Syria. Every day hundreds of people were arriving in the camps. Who was left back home to help those most in need? So I decided to return. This time it took me three weeks to reach the Qalamon Mountains north east of Damascus.

Back to Syria

Back in Syria I met the famous Serbian photographer, Goran Tomasevic, who took me on as his fixer. I would organise his schedule and help with the equipment. I told him that I’d been an amateur photographer so he took me under his wing and taught me everything about how to capture a country at war. Every day for two months we would go up to the frontline and take pictures of the FSA.

Goran was crazy, he didn’t seem to feel fear. One morning in early January a sniper’s bullet missed my head by millimetres, he just turned to me and laughed, “Luckily you are so f***ing short”. When he was happy with my work he introduced me to Reuters and I started my career as a photojournalist. Neither of us chose this job but when our countries were burning we picked up a camera.

Neither of us chose this job but when our countries were burning we picked up a camera.

I would wake at 4 am and wait for one of the rebel soldiers to call. They would tell us where the fighting was likely to be and where we could join them. It was risky work and frightening seeing death and killing so close up. One day we were at the front line in Maleha waiting in an empty building. There was a big echoey hall that the rebels used to cross from one room to the other. Suddenly from the other side two or three grenades came whistling through the air, followed by heavy artillery barrage. The rebels fired back. Bullets were flying everywhere. For 30 minutes there was no let up. Very slowly we inched into a cupboard in one of the back rooms. I cannot believe we got out of there alive.

When my photos began to appear on the front pages of newspapers like The Daily Telegraph and the New York Times, alongside Goran’s, I felt funny and proud. I am just a civilian, I am not a soldier, I am not a fighter.

On my way to shoot a local military brigade I was hit by a shell. One moment I was walking down the street, the next I was in the air. They said I was out cold for about 20 minutes. I had done first aid training in Lebanon so when I came round I knew it was bad. My knee, thigh, shoulder, all the right side of my body were badly damaged. I was put in clapped out ambulance, with all the glass blown out. As it careered along I leaned out the window and directed the driver away from the pot-holes.

I was confined to bed for two months. I was in pain but also bored being housebound so I pestered my friends to take me out. Reluctantly they would push me towards the frontline in my wheelchair so I could take photos. In May I went to a doctor to take out the pins in my knee but because he wasn’t properly trained he rebroke it and I was back in bed again.

Once I could walk I returned to the streets with my camera and my stick.

Ghouta, the little sis of a friend. ‘Knowledge is the light’, the girls said when asked why they did not wait till morning light.

© Artino (Oct 2013)

Ghouta August 2013

In August 2013 I witnessed the now infamous chemical attack in Ghouta. I was woken in the middle of the night with news of a gas attack. The next morning despite several warnings not to go, I went to investigate for myself. Nothing prepared me for what I saw: children, babies lying on the floor in their pajamas, so still and calm with no visible signs of injury. They looked like they were sleeping but all around was mayhem: everyone screaming and crying, but the children so still and other worldly. I noticed their strange complexion and they had fluid coming out of their mouth and eyes. They were all dead, I wasn’t able to count them all. They say more than 400 children were killed.

I was paralyzed. I couldn’t move, let alone take a picture. As the feeling of nausea ebbed away I realised I had to do something. When I found a doctor I asked him, “How can you be sure this is chemical and not a normal death?” He himself was in shock, minutes before his colleague had died after inhaling the sarin. He carefully showed me the dark blue colour on their skin; the foam and vomit around their mouths were the signs of asphyxiation. This was a war crime.

Because there weren’t enough hospitals the bodies had been laid out in schools and mosques, rows upon rows of them. I wandered from one building to the other documenting what had happened so this terrible episode could not disappear into history. Something inside me broke: so many victims, survivors hallucinating and gasping for breath. Hell came to Eastern Gouta that day. Barack Obama said that if Assad used chemical weapons on his own people there would be no other option but to intervene. We are still waiting.

Six Pack Under Siege

I broke my knee for a third time. With no fuel or medical equipment doctors were reverting to very primitive forms of medicine. I walked around with a branch strapped to my leg for support.

This was a difficult time. The whole area was being besieged by government forces. The siege was getting tighter and the food we had put by wouldn’t last long for the three of us. None of us choose to abandon our homes but sometimes we run out of options. Syrians don’t want to be tagged as refugees or displaced persons but as long as this policy of ‘starve or surrender’ continues we have to make very difficult choices. My parents are in their fifties and living in a warzone is a huge burden. I had to make a decision, we all did. I persuaded my parents that they should leave Ghouta.

88 years old he was. Every day I saw him, and we talked. 1 of his sons was in the FSA, the other in the regime army.

© Artino (April 2014)

I began reading avidly, finishing a novel almost every day. I started manically searching the internet on how to survive under siege.

Left alone for two months with a broken knee, I had to fend for myself as best as I could. I would crawl across the floor just to reach the bathroom. It was tough and humiliating but more than that I was fed up. Self pity and depression were setting in, I needed to do something. I began reading avidly, finishing a novel almost every day. I started manically searching the internet on how to survive under siege. But it wasn’t enough, I was powerless and my body wasn’t mine anymore. Then it hit me, I could still working out and maybe get a full set of muscles!

I decided that if I could I could improve my body it would have a positive impact on my mental state. So I started a workout program focusing on my upper body strength. It was shortly after my thirtieth birthday, what guy wouldn’t want a six-pack. Did it matter that I was living under siege, in a country at war - No! As I posted the photos on Facebook, my friends commented wildly, they have seen too much blood and bullets, this was different, funny even, my quest for a beautiful body. One of my friends even published an article: ‘Six pack under siege’. Bit by bit, I started to gain strength and move again. I was proud of my abs, perhaps they weren’t perfectly sculpted because I didn’t have access to enough protein or fat to build the muscle, but it was still impressive. It may seem strange that while my neighbors were scrambling to find enough food to feed their children, I have no food also but I was worrying about how I looked, but this is what extreme situations do to you.

Farewell to a camera

The calcium in my knee was decomposing, and the only long-term option was a knee transplant, impossible in Ghouta. Every time I went to the field hospital to get my screws fixed, I could see my case wasn’t a priority; people with life threatening conditions couldn’t get enough medicine. Hobbling around on a stick I was doing some volunteer work distributing food and teaching photography to children but I couldn’t walk more than a few metres. The pain was unbearable.

Leaving this time was probably the worst. I was abandoning people who were relying on me. And I also had to let go of my camera. It had been part of me for two years: my eyes, my witness, my tools. I kissed her goodbye as I would a daughter and passed her on to a friend and fellow photographer for safekeeping. She still has a part to play.

Lebanon II

I paid a smuggler $4,000 to to provide me with a fake Syrian ID and take me from Eastern Ghouta to Lebanon. The journey took almost a month. With the injury I couldn’t move fast and the fighting was on all sides. We had to dodge the different armed groups, sleeping in bombed out buildings or sometimes outside.

My friends in Lebanon gave me a warm welcome. It had been two years since I had been there – so much had changed. After the bombs, the cold and hunger I felt myself surrounded by luxury. When I asked my friend for a glass of water I expected him to go over to the sink and fill the glass but as he opened the fridge and the light flicked on, I broke down and wept. I was so overwhelmed and exhausted.

Resettlement

As I tried to establish my life there I found I was forgetting small things: names and appointments. I was diagnosed with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder so I went back to volunteering in order to keep balanced. I still hadn’t been able to get my injuries fixed. I then learned of another option, resettlement. So I applied for, and was granted settlement in Europe. They say, “being a refugee is not a choice”, and I truly believe that.

I’ve only seen one camel in my life. I am just a regular metalhead, tattoos and all.

I arrived in Belgium towards the end of last year. The people have been warm and friendly. They’re astonished when I tell them I am Syrian. They have this image that Syrians are all jihadis living in the desert with the camels; I’ve only see one camel in my life. I am just a regular metalhead, tattoos and all.

I learned my half brother was killed in action towards the end of last year. He was a pro-regime fighter, and died defending what he believed in. I haven’t spoken to that side of the family since the start of the uprising. My older brother is also in the army. He’s probably too old to fight now, and instead works for the ministry. Back in 2012 he saw my picture on TV attending the funeral in Homs, we were still naive and didn’t know we should be covering our faces. He texted me to say that I was a disgrace to my family and if he ever found me he would kill me. We had always had a difficult relationship, he would taunt me when I was a kid and blamed me for killing his mother. A couple of years ago he sent me a message to say he knew I was out of the country. Was this another threat? He is so loyal I feel sure he would still kill me if he could.

The civil defence in action after a car bombing. Hope one day my medical situation allows me to work as a civil defence volunteer.

© Artino (June 2014)

My natural father died in 2014. While he still backed the regime of Bashar al Assad he had accepted our differences. When he secured my release back at the start of all this he told me that he was proud of me, “Your uncle has done a good job, he has ensured you got a good education and you have inherited his good nature.” He pleaded with me to give it up but knew I probably wouldn’t. He told me he was able to save me once, but if I got caught again there was no more strings he could pull.

Last week I finally had my surgery, three years after my knee was first damaged by the shell. When I am physically fit I will go back home.

I miss home. Of course I miss home.

Maak MO* mee mogelijk.

Word proMO* net als 2793 andere lezers en maak MO* mee mogelijk. Zo blijven al onze verhalen gratis online beschikbaar voor iédereen.

Meer verhalen

-

Report

-

Report

-

Report

-

Interview

-

Analysis

-

Report

Oxfam België

Oxfam België Handicap International

Handicap International