Return to Aleppo with Roni, Syrian refugee in Belgium

‘Maybe I should never have returned to Syria’

© Emiel Petrovitch

© Emiel Petrovitch

Seventeen years after fleeing Syria, Roni Hossein returns as a Belgian citizen. What begins as a pilgrimage to his grandfather’s grave becomes a stark, personal journey through loss, regret, and a tentative hope for national reconciliation. In Syria, the wounds left by dictatorship and war remain far from healed.

At the Syrian border, the songs of the revolution echo through the air. “The homeland welcomes you,” flashes across a screen. Border guards greet travellers with polite smiles, as if welcoming back old friends. The taxi races down the straight desert road, as though the driver hopes to help Roni reclaim the years he lost.

He turns up the volume. “Hold your head high, you are a free Syrian,” the chorus rings out. Roni plays a video of his Belgian-born daughter singing the same song. With a cautious hope settling in his chest, he heads toward the traumatised nation behind the barrier.

Along the road, trucks from Jinderes pass, the northern town where his family’s roots lie. His ancestors planted thousands of olive trees there. In the mountain village of Kurdan, Roni’ beloved grandfather Wahid was buried while he was in Belgium. His grandfather’s grave is the final destination of this journey.

© MO* (CC BY 2.0)

Damascus

The next day, in a noisy café where Real Madrid and Atlético battle it out on the screen, Roni meets his childhood friend Mohammad Dabag. Mohammad lives in Jaramanah, a neighbourhood in Damascus. “This is Syria in miniature,” he says. “Kurds, Arab Christians, Druze and Sunnis live alongside one another here. We won’t give that up.”

In Jaramanah, Roni feels free to smoke and drink water in the streets, behaviour that can seem inappropriate elsewhere during Ramadan. Armed men guard the access roads, while daily life carries on behind the checkpoints. Since the fall of the Assad regime in early December 2024, the neighbourhood has been controlled by a Druze militia. Mohammad is not Druze himself, but he shares their distrust of the new Islamist rulers.

Mezzeh, another district, was once Assad’s power centre and is now controlled by interim president and Islamist leader Ahmad al-Sharaa. A billboard near the Ministry of Information reads: “Brotherhood without borders.”

The guard at the gate is a Sunni from Latakia, on the coast. Would he count among those “brothers” the Alawites who were recently subjected to brutal attacks there? Roni thinks of the summary executions of unarmed people carried out just before his return to Syria. “Alawites from Latakia used to hold administrative positions,” he says. “Now Sunnis hold power. The roles have been reversed.”

On the outskirts of Damascus, the city noise fades until only the skeletons of collapsed buildings remain. It is Roni’s first direct encounter with the destruction wrought by former president Assad and his Russian allies. He looks around in silence. “What lives inside people who have suffered like this?” he whispers, fear in his voice.

Hope in encounter

That fear soon gives way to hope when he meets someone from that world in Deir al-Asafir: Mohammed Akkar. In 2013, Akkar helped establish a local civic council in rebel-held territory. When Assad and Russia retook the area in 2018, he and hundreds of thousands of others were forced north. He eventually settled in Afrin, Roni’s home region.

There, Turkish President Erdoğan allowed Arab refugees like Mohammed to move into the homes of expelled Kurds, a demographic move aimed at breaking the Kurdish majority.

A great deal converges in this encounter: fourteen years of using people as pawns, of mutual violence and revenge.

Roni approaches carefully. Only when he senses tolerance does he dare say he is Kurdish. Not long after, Mohammed and Roni walk together, arm in arm, through the ancient Roman olive groves surrounding the ruined town. Two men who had lived for years under the shadow of presumed hatred, only to find in each other a quiet longing for reconciliation.

Roni recalls his high-school days under the Assad regime. During the “National Lesson,” everything revolved around the Assad family. The country’s cultures and ethnic groups were never discussed. “We learned nothing about each other. Nothing. That makes it easy to spread fear.” Mohammed nods in agreement.

Roni meets Mohammed Akkar (left), an Arab Syrian who was expelled to Roni's native Afrin and who returned to Deir al-Asafir near Damascus after the fall of Assad.

© Pieter Stockmans

Aleppo

Roni tosses under the sheets, eyes wide in the dark. “I can’t sleep,” he whispers. “Stress. Stomach pain. Tomorrow I’m going to Aleppo, my city, where my childhood home is. Everything is circling in my head: sadness and anger over what I’ve lost, joy because I can return, fear of what I’ll find… all at once.”

The next day, his suitcase rattles across the tarmac. Sheikh Maqsoud, the Aleppo district where he grew up, lies just a few streets away. Cars speed by. His niece Bahar, seventeen years older than when he last saw her, waits by her car.

As they inch through the heavy traffic, Roni shows her a photo of a curious encounter from a few days earlier. A commander from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, whom we had interviewed at his base, turned up that same evening at Damascus’s oldest ice-cream parlour in the Al-Hamidiyah Souk. In the banality of that moment, Roni glimpsed a trace of shared humanity and allowed himself a fragile hope: that even jihadists might widen their narrow worldview now that they rule over Syria’s complex mosaic.

A commander of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham eats an ice cream at Syria's most famous ice cream parlor.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Sheikh Maqsoud is a Kurdish-controlled enclave in the middle of Aleppo. Sandbags are piled haphazardly around its entrance gates. As Bahar approaches one of the checkpoints, a member of the Kurdish YPG militia signals her to stop. His colleague, adopting an air of superiority, asks for our papers. For Roni, who spent a quarter of a century of his life here, it feels as if he must ask permission to enter his own past.

Amid the crumbling concrete slabs, vegetable sellers stand behind makeshift stalls. People weave casually through a landscape of destruction. The rubble has become part of everyday life.

Bahar welcomes her cousin with an iftar meal that costs an entire month’s wages. “Monthly salaries mean nothing here,”she says. “Wages are low, prices are high, and money is worthless. No one survives on a salary alone.”

Suddenly their conversation is drowned out by drums and cheers: the Kurdish New Year festival, Newroz, has begun. As the sun casts an orange glow over the neighbourhood, young people dance around fire pits, waving flags of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF, of which the YPG is a part). Giant portraits of Abdullah Öcalan, their spiritual leader, hang from building facades like icons.

Roni’s silence and visible discomfort stand in sharp contrast to the festivities. “Not a single Syrian flag,” he notes. “Only SDF and YPG symbols. This will turn against us one day, just like it did for the Alawites and the Druze.”

In 2013, a divide opened between Kurds who supported the Syrian revolution and those who believed in the so-called “Rojava revolution.” Backed by the Turkish-Kurdish PKK, the latter built their own army (the SDF) and autonomous administration. Roni counts himself among the first group. In 2011, he demonstrated for the Syrian revolution in Brussels. Even when Islamists hijacked the uprising, he continued to believe in liberation for all.

“I saw the east of Damascus completely flattened by Assad,” Roni says. “People living under the control of Sunni Arab rebels were besieged for years. It makes sense that they now hold power too.”

“But,” Bahar argues, “the rebels started it and Assad responded. It’s their own fault.” Roni is shocked, but tries to understand. Bahar lived under rebel rockets and their open hostility toward Kurds.

In the car on the way to the apartment where Roni grew up, Bahar sings along to Bruce Springsteen’s Dancing in the Dark. The song pulls Roni back to the 2000s, when he founded Aleppo’s first modern dance collective with his close friends Ahmad Mamo and Rezan Abdou. Then came the fateful day in 2008. After their final performance, about “the Seat” to which dictators cling, the darkness closed in. On the run from the notorious secret service, Roni had to say a hurried goodbye to his family and his life, fleeing via Turkey to Belgium.

Four years later, the war brought him countless sleepless nights in Leuven. He tormented himself with fear that his parents, brother and sisters might be killed. Despite his father’s stubbornness, they too eventually placed their fate in the hands of people smugglers. After a degrading journey that lasted nearly two years, they were finally reunited with Roni in Europe.

Just as Springsteen’s song fades out, they arrive at the apartment. There is no electricity, only the cold blue glow from a generator. Roni scans his surroundings tensely. Everything looks more chaotic, dirtier, more alien. Then, suddenly, he recognises the stairwell where he played football as a child.

His hand trembles as he knocks. What will he find? Hospitality, or hatred and distrust? The door opens. The new residents are understanding, almost apologetic. But as soon as Roni steps inside, his breath catches. The house is empty, cracked, dismantled. Only mattresses lie on the floor. Where a sliding door once separated the living room from the bedrooms, there is now a gaping opening. And just where he used to play behind a flickering computer monitor, soldiers have carved a passage through the wall.

Roni visits his childhood home after 17 years, which he had to flee in 2008. Other people live there now. Nothing tangible remains of his memories.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Roni found old photos of the house at his uncle's house.

© Emiel Petrovitch

The balcony is smaller than he remembers. “In summer, I used to sleep here,” he says. “The curtains fluttered in the wind. Everything was a hundred times nicer. My mother was obsessed with cleanliness, she made even the walls shine. Now the paint is peeling.” He searches for something tangible from his childhood, but finds it only in the form of an old scar on his own face, earned when he fell from a cupboard as a small boy.

And in the person of Amina, the mother of his close friend Ahmad Mamo.

Amina has been left alone, without husband or son. When Roni sees her, he is thrown back in time. He remembers how Ahmad once got them tickets to an exclusive performance at the Damascus Opera House. They were soldiers then, entering the opera house in army boots and with shaved heads.

The performance was called Dead Can Dance. Years later, Ahmad himself would become a “dancing dead.” On 22 March 2014, he was killed in a rocket attack by Al-Sharaa’s Nusra Front on Latakia.

At the time, Roni was in Belgium, searching in vain for the artistic self he had left behind. He had been forced to start from scratch, pursuing a new education that promised quick employment. Over the years, he grew convinced that nostalgia destroys a person. He had sealed off his old life in a dusty box.

But now, standing before Ahmad’s mother, he again sees the boy who once moved so lightly across Aleppo’s stages. He sees the man he could have become.

And he thinks of Rezan, the refined, sensitive friend he last saw in Istanbul in 2015. Rezan scraped by as a street vendor, was later resettled as a refugee in Canada, but never managed to settle. He fell into depression and eventually died from it. Now Roni, the sole survivor of the inseparable trio, is back in Aleppo. His city, inhabited since time immemorial, is today a physical and psychological ruin.

“Which is worse?” he asks himself. “Losing everything and living with sweet memories? Or standing face to face with the shadows of yourself and your family in a shattered place? It feels as if the person I once was had died inside me, and now I am desperately trying to revive him. Only now do I really feel what the war has done. Maybe I should never have come back. Maybe I should have kept Syria alive only in memory.”

In 2015, Roni said goodbye to his close friend Rezan in Istanbul. He would never see him again: Rezan died a few years later in Canada.

© Xander Stockmans

Along Road 62

Bahar’s father Mohammed, Roni’s uncle on his father’s side, is not allowed to enter the district with his car. His licence plate is registered in Afrin, which has been under Turkish occupation for seven years. The SDF, the militia that controls Sheikh Maqsoud, was driven out of Afrin by Turkey. Here, they take no risks.

The road from Aleppo to Afrin, Road 62, was a closed artery for years. Since the fall of Assad, it has reopened, though the scars of war and division remain everywhere.

It was along this road that the Assad regime’s collapse began in November 2024. The Turkish-controlled factions in Afrin formed a front with Al-Sharaa’s forces in Idlib. Using Road 62, they advanced toward Aleppo. “I drove here that day and had to zigzag between the corpses of Assad soldiers,” Mohammed recalls.

Posters of fallen fighters from the Turkish-backed factions line the route. Mohammed reads the word “Martyr.” He gives a wry smile. “These occupiers didn’t die for Afrin. They committed horrific violence against the Kurdish people.”

Step by step, the new Syrian government is taking Afrin back from those groups. This makes Mohammed feel somewhat safer, though he concedes he may be experiencing a kind of Stockholm syndrome. After all, the new army is made up of jihadists who have already shown that their ideology and personal thirst for revenge, against Alawites and Druze, can outweigh their new role as supposed neutral protectors of all Syrians. It is a choice between plague and cholera.

But Roni and his uncle flinch at any hint of separation, whether by the Kurdish side or by pro-Turkish militias. Mohammed knows all too well what separation brings. For eight years, he was kept apart from his daughter. In 2014, at the height of the war, Bahar was studying in Aleppo barely 60 kilometres away, yet cut off behind impenetrable front lines and checkpoints. They were only reunited after the fall of the Assad regime.

From Aleppo, Bahar became mayor of several Kurdish hamlets controlled by Al-Sharaa. She points to the road. “There is one of my villages, Ghazzawiya. Each village had two mayors: one from the Assad regime, and one from the Al-Sharaa Islamists. I could not enter that area. Official administration was still handled from Aleppo city.”

Suddenly, Bahar receives a PDF on her phone: a letter of resignation from the new authorities in Aleppo city. All Kurdish village mayors around Afrin have been dismissed. She reads silently. It had been coming: the new government under interim president Ahmad al-Sharaa is replacing the mayors of the old regime.

At the same time, news appears on Facebook: “A government delegation will visit the autonomous Kurdish areas.”“That’s alright,” says Roni. “They are talking. There might be less chance of war.”

Roni reunited with his uncle Mohammed at Qalat Semaan, the ruins of a 5th-century Byzantine church complex near Afrin.

© Pieter Stockmans

The taste of peaches in Bassouta

Hanifa, the sister of Roni’s late grandmother Khadija, lives in Bassouta on the road to Afrin. Hundreds of thousands passed through this hilltop town while fleeing the Turkish bombings of 2018, transporting their belongings on pick-up trucks into areas still controlled by the YPG.

Hanifa stayed, and paid a price. Her son Marouf, who once ran the most popular restaurant in Bassouta and the surrounding area, now stands alone in the empty hall where guests once enjoyed fried fish and the murmur of the river. He shows a video of planned expansion work. “Everything was paid for,” he says. “Materials, architects. The plans were ready.”

But with every bomb, the reality sank deeper: there was no future, only the struggle to survive. They fled for twelve days. When they returned, everything had been looted. Then the occupiers came, like true mafiosi, to demand protection money.

Even the YPG did not leave them alone, Hanifa adds. Her other son fled to Lebanon to escape conscription.

Hanifa disappears into the kitchen and returns with coffee, biscuits, and fruit. Roni catches up with his mother, Khadija’s daughter, via his phone screen. From the balcony, he lets her share the view over hills full of apricot and peach trees. “It’s strange,” he says, “but seeing Aunt Hanifa, I suddenly remembered the taste of those peaches.”

Roni shows a photo of his son in Belgium during a visit to "aunt" Hanifa, his grandmother's sister.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Hanifa (left) stayed in Bassouta, but paid a price. Her son's restaurant was looted, and her other son fled to Lebanon to avoid fighting.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Afrin city

On Roni’s smartphone, the network Turk Telekom appears. Along a road winding through olive groves, a checkpoint is marked with murals of the Hamza Division, one of the Turkish-controlled factions occupying Afrin.

“Move aside! Wait!” shouts a masked soldier. Mohammed stresses. Roni presents his journalistic accreditation and the photo of the commander he had met at the Damascus ice cream parlour a few days earlier. “We sat there with the new leaders. He said we could call him anytime. Should I do that now?” Roni asks briskly.

The soldier’s tone softens. He removes his mask and smiles. “Brother, we are only doing this for your safety. No problem.”

Mohammed laughs bitterly. He knows the reality: without connections, you are a bird for the cat here. He has been extorted multiple times at checkpoints like this.

Battal, the brother of Roni’s grandfather Nouri, witnessed masked soldiers and civilian invaders arrive and leave quietly. “They came with one suitcase and left with trucks full of looted goods,” he recalls. “I was once in an IT shop when someone from those militias came in with a laptop he wanted to sell. They were selling things taken from our houses. I saw militia soldiers going from house to house with locksmiths.”

“We live in fear, without family, in a broken and occupied economy.”

That is why Battal guarded his brother Nouri’s house, after Nouri fled to Belgium. During the Turkish invasion, a rocket struck straight into the living room. “My son slept there that night,” Battal points out as his wife serves dinner in front of the bricked-up hole in the wall. “The missile just came right through. If it had exploded, he would have died instantly.”

The missile remained in the room for days. Turkish soldiers eventually came by, not to pay for the damage but to collect their rocket. “They could then throw that on another house,” Battal says bitterly.

Battal remained on his native soil, but lives far from his emigrated children. His brother Nouri was uprooted and lives far from his olive trees that he considered his children, but does live close to his family in Belgium. Who is better off? Battal has no doubts: “Nouri,” he says. “My grandchildren I have never seen. Outsiders only see the beautiful nature here. But we live with fear, without family, in a broken and occupied economy.”

The olive harvest is their main source of income. “Everything here has become more expensive, except olive oil. Strange, isn’t it? The processing plants were taken over by the occupiers. They artificially lowered the price Kurdish farmers get, then export to Turkey at a profit. They work for Erdoğan (the Turkish president, ed.). Afrin could build a strong economy, but is deliberately kept weak and dependent.” On the way, we saw one such company with the Turkish flag on it.

© Emiel Petrovitch

The next morning, coffee is steaming in the sun on the spacious balcony. Roni is leafing like mad through old photo albums he found in a cupboard. The dusty box of his old life opens wide.

“I'm not properly awake yet, I haven’t even washed my face yet,” he laughs. Criss-crossed are yellowed photographs of domestic scenes and formal family portraits.

Among the pile is a special photograph: the living room of the apartment in Sheikh Maqsoud. White decorative curtains, wooden furniture, indoor plants, birthday cakes, fruit bowls, soft drinks, family members united in what was then their life. Years later, it would shatter like rubble from a bombed-out building.

“This picture is over 30 years old,” says Roni. “It’s from the late 1990s, Hafez was still president. All the people in this photo are now uprooted, scattered across Belgium and Germany. And here you can see my grandmother Fadila. She spent her whole life with my grandfather Wahid in the mountains among the olive trees, but she died and was buried in Stuttgart.”

Jinderes

Roni is heading toward the mountains where his roots lie. Jinderes, the town at the foot of Mount Kurd in the Afrin river valley, was severely damaged by the massive earthquake of 6 February 2023. Behind the battered row of shops on the main street lies rubble. Collapsed housing blocks stand as skeletons, while tents serve as makeshift homes where mothers dress their children. Since 2022, private lives have been lived literally on the streets.

“In that building, rescue workers found bodies under the rubble only after a month,” says Mohammed. “So many international aid organisations came to Jinderes. The relief effort was pure chaos. Some people who had lost everything received nothing. Others just came to benefit.”

Mohammed stops at a street corner to fill a container with diesel using a funnel. “Exactly two years ago, also during the Newroz festival, four revelers were shot dead here by Turkish-controlled factions. All of Jinderes revolted. The perpetrators were arrested, but later simply released.”

For seven years, Jinderes has been under Turkish control. “What do you notice here?” Roni asks. “Turkish flags painted on shops, women walking in niqabs, things we never used to see here. They are Arab families driven out from the south.”

Roni at the olive grove in Kurdan, the mountain village of his grandfather Wahid (the man on the right in the photo below).

© Pieter Stockmans

In the mountains around Jinderes, Roni gestures to his uncle Mohammed to stop by his family's olive groves. Every autumn, they came here from Sheikh Maqsoud to harvest olives: burning bad branches, removing stones from under the trees, and picking olives.

Holding an olive branch, he gazes over Mount Kurd, where the green dots reach to the horizon. Is he the dove of peace who takes the olive branch home, as proof that the war is over and the return to Kurdan is once again possible? That is his dream, but the reality is different, after the recent flare-up of violence.

Kurdan, village of an uprooted family

The journey continues to Kurdan, a cluster of ancient stone cottages clinging to the mountainsides around a hidden valley. As Roni drives into his grandfather’s village, rain begins to fall. “The foreigners have brought rain, thank God!” exclaims Mohammad’s son Delshad. Roni last saw him as a small boy, now a young adult stands before him.

A few years ago, Delshad attempted to reach Europe from Turkey, but failed. This village has seen many sons and daughters leave. “My children are in Austria and Germany,” says a woman buying shampoo in Mohammed’s shop. “And mine are in Istanbul and the Netherlands,” adds the neighbour Tawfik.

The centuries-old family house was dying during the war. The walls cracked in the earthquake. Mohammed invested his savings into repairing the half-collapsed facade. The house was gutted, emptied of the people who once brought it to life. It was only on 8 December 2024 that life slowly returned. After Assad’s fall, Mohammed reunited with his children Delshad and Bahar for the first time in years.

But the war changed them. Delshad came into contact with Afghan Islamists in Turkey and embraced the faith. Bahar, by contrast, spent years in Aleppo under Islamist missiles and developed an aversion to religion. Their younger sister Sevin, who stayed in the isolated village, embodies peace.

Paradoxically, Sevin is the only one who speaks English, having learned it over the phone because the war limited her schooling.

The family of Roni's uncle Mohammed, reunited since the end of last year. From left to right: Mohammed, Nazli, Bahar, Delshad, and Sevin Hossein.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Sevin stands in her party dress in the courtyard, ready to leave for the Newroz festival at Lake Maydanki. At the start of spring, the reservoir traditionally hosts the Kurdish New Year; in summer, it was a haven under the shade of trees.

When Sevin was 11, during the Turkish invasion of 2018, the area was still covered in lush forests. In five years, they had been stripped bare, timber looted and sold by Turkish-controlled factions. The spring festival, a three-thousand-year-old tradition, had been banned for years.

But in 2025, it is allowed again. The influx is massive. Traffic to the lake takes longer than the festival itself. People dance in giant circles to rousing music.

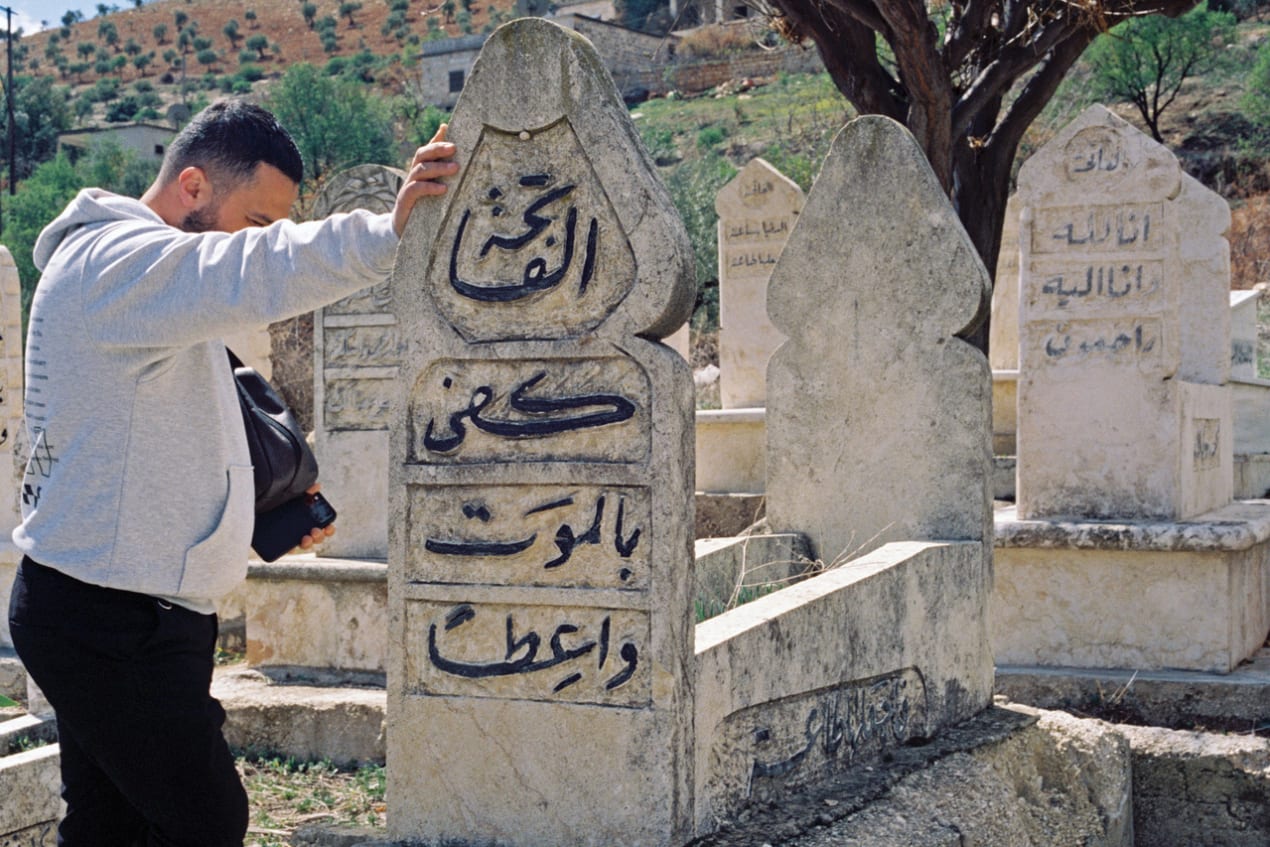

Grandfather Wahid’s grave

The next morning, Kurdan awakens as the sun rises behind the hills, slowly bathing the valley in light. Both of Roni’s grandparents hail from Kurdan: the Hossein family and the Jafar family. Their parents and grandparents lived here as well. Grandpa Wahid’s father built the house at the start of the 20th century. As children, Roni’s parents, Ahmad Hossein and Nazlia Jafar, were neighbours across the street.

When he fled Syria in 2008, Roni said goodbye to his grandfather in the mountain village of Kurdan. His return was a reunion at the grave.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Behind their houses, a steep path winds down to the cemetery at the valley’s base. The graves stand as silent, white witnesses to Kurdan’s founders, framed by the green olive trees that are their legacy. This is where Roni’s family story began generations ago.

On his grandfather Wahid’s grave is inscribed: “Life is an hour.” The days pass so quickly that one day you are buried beneath the earth. In the silence, everything is said: what they endured and lost, what they managed to preserve, and how they overcame uprootedness to build new lives.

After a moment of silence, Roni speaks, his voice thick and tears in his eyes. “The night before I returned to Syria, my father in Belgium said, ‘I only want one thing: for you to go to my father’s grave.’”

At the grave, he addresses his grandfather: “Consider yourself lucky, you didn’t live through that ugly war. At least you are in the soil of our village. Nouri lives far from here, in Belgium. He fears he will be buried abroad like your Fadila. Your whole life was spent with grandma in this village. Until the last second, she took care of you. And now, after your death, you are separated. That’s so hard.“

“You used to say, ‘Roni, you are the first grandson of our family. Never forget our land. The roots of the trees here are also our roots. Our families planted them.’ But my roots have been cut. Returning is difficult after a seventeen-year void.”

“But even my children, your great-grandchildren, born in Belgium, are connected to this place. Someday I will come with them to your grave. I only once saw you cry, when I came to say goodbye the night before my flight in 2008. I kissed your hands and left. I never saw you again. But I have kept my promise.”

This article was published originally in Dutch in september 2025

Translation: Pieter Stockmans

If you are proMO*...

Most of our work is published in Dutch, as a proMO* you will receive mainly Dutch content. That said we are constantly working to improve our translated work. You are always welcome to support us both as a proMO* or by supporting us with a donation. Want to know more? Contact us at promo@mo.be.

You help us grow and ensure that we can spread all our stories for free. You receive MO*Magazine and extra editions four times a year.

You are welcome at our events free of charge and have a chance to win free tickets for concerts, films, festivals and exhibitions.

You can enter into a dialogue with our journalists via a separate Facebook group.

Every month you receive a newsletter with a look behind the scenes.

You follow the authors and topics that interest you and you can keep the best articles for later.

Per month

€4,60

Pay monthly through domiciliation.

Meest gekozen

Per year

€60

Pay annually through domiciliation.

For a year

€65

Pay for one year.

Are you already proMO*

Then log in here