In Syria, armed boundaries are blurring

‘We are not going to lose another hundred years, our moment is now’: will Syria become one again?

The Kurdish flag and the new Syrian flag at a demonstration in Afrin against the Turkish occupation.

© Emiel Petrovitch

The Kurdish flag and the new Syrian flag at a demonstration in Afrin against the Turkish occupation.

© Emiel Petrovitch

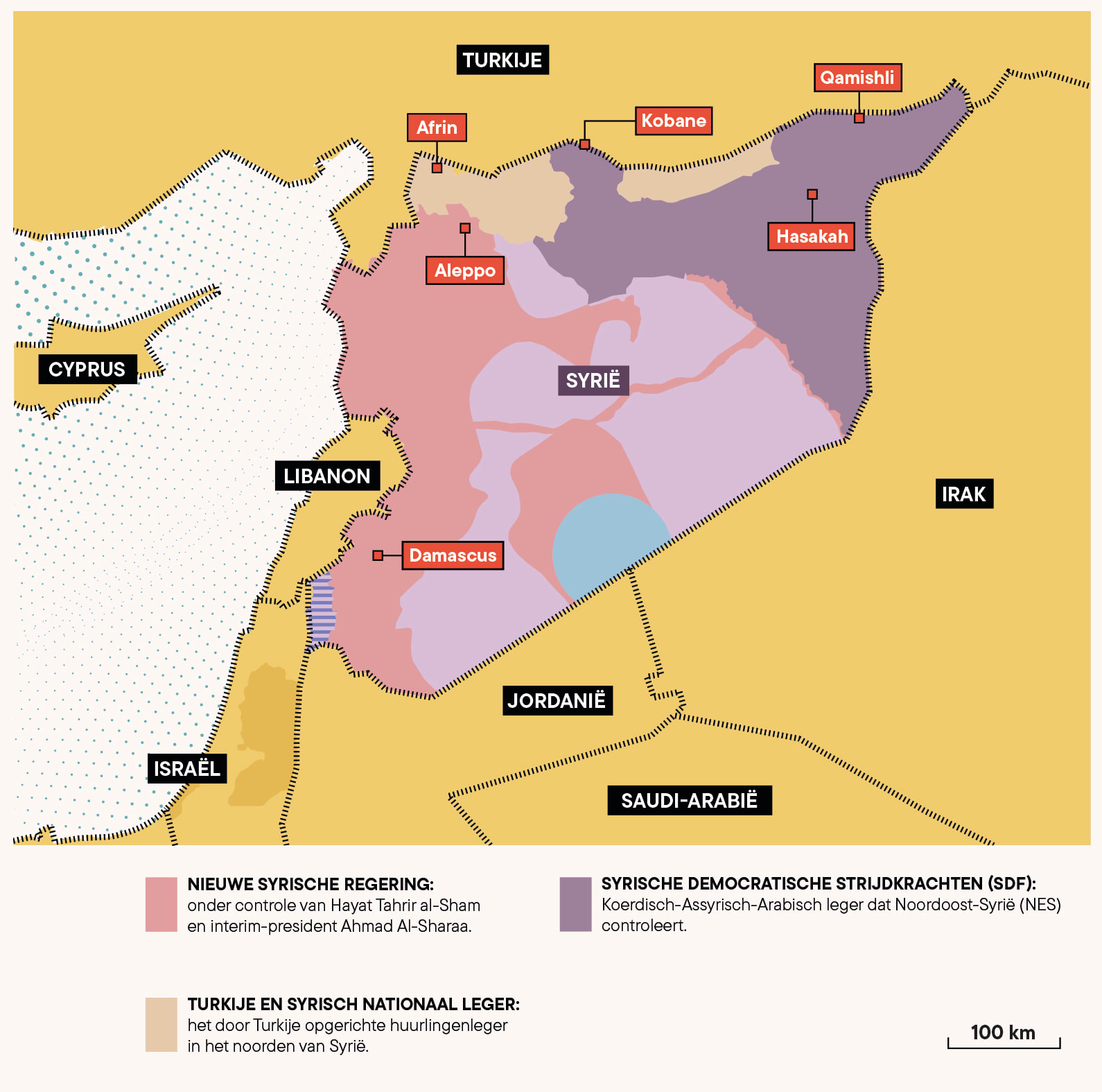

In Syria, borders once drawn by force are blurring. MO* visited the three areas controlled or lost by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). What seemed unbridgeable is now being redrawn at the negotiating table. Is a federal Syria emerging here?

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

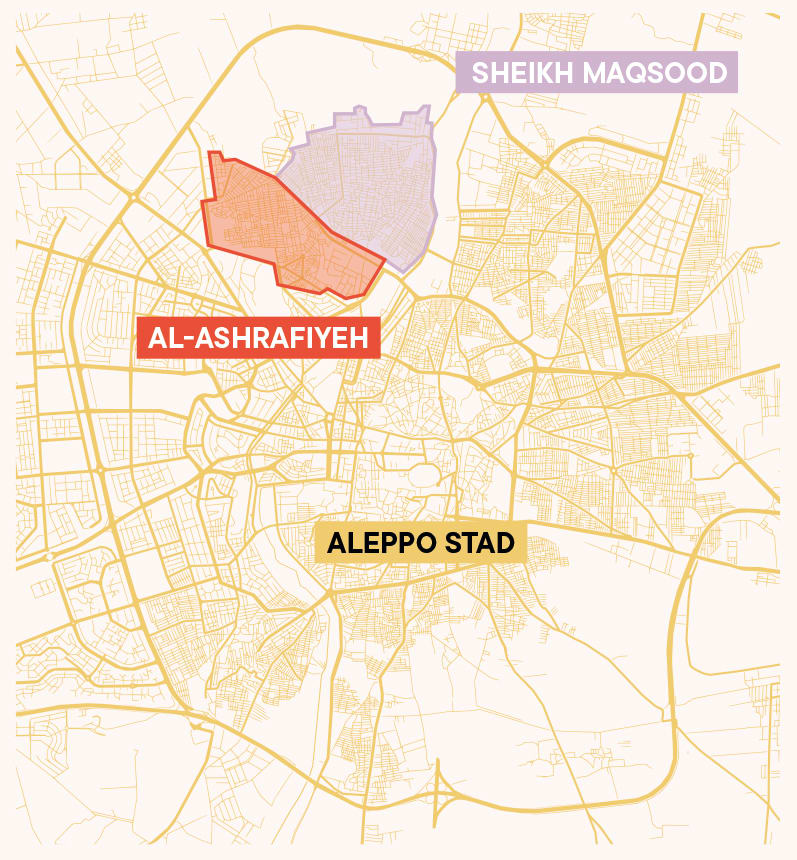

‘Get off’, snarls the soldier. ‘No pictures. What happens here stays here. We know where to find you.’ The hope sparked by the 10 March agreement between the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the new Syrian government under interim president Ahmad Al-Sharaa now feels far away. We are in the Sheikh Maqsood district, controlled by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (NES). It is a gated enclave in the heart of Aleppo, inhabited mostly by Kurds. At a checkpoint, SDF soldiers inspect every vehicle.

Sheikh Maqsood is a maze of streets. Chaos reigns on the main road due to the Ramadan festival. Kurdish police zip past on mopeds. Among the half-destroyed apartment buildings – only the mosque has been repaired – there are market stalls and humming generators. On the outskirts of the neighbourhood, young people smoke water pipes, facing sandbags and walls of mistrust.

Above: Chaos reigns on Sheikh Maqsood's main street due to the Ramadan festival. Below left: At a checkpoint, SDF soldiers inspect every car. Below right: Sandbags are strewn around the neighborhood.

© Emiel Petrovitch

© Studio Verho

© Studio Verho

Aleppo, divided city

When the Kurdish YPG militia, following a deal with Assad, settled in Sheikh Maqsood in 2012, heavy fighting broke out. Later, the group merged into the SDF. ‘For years, Free Syrian Army rockets flew past our ears’, says Bohar Hossein, mayor of six Kurdish villages. When the war began, she was still studying in Aleppo. She was unable to visit her family in the mountain village of Kurdan, in the Afrin region less than 60 kilometres away, for eight years. Only after Assad’s fall did the road between Aleppo and Afrin reopen.

On her table lies a photo, dated the last day of the Assad regime. ‘We woke up in another country’, she says. ‘We were crying with fear. It was a good thing the YPG kept control, because we cannot live under jihadists.’ From Bohar’s balcony, we hear the music for Newroz, the Kurdish New Year. At a roundabout, a crowd dances around a fire. A life-size portrait of PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan hangs on a wall. The Syrian flag is absent. Many Arab Syrians call the SDF ‘separatists’ and have threatened attacks.

Residents of Sheikh Maqsood celebrate Newroz, the Kurdish New Year. A life-size portrait of PKK leader Abdullah Öcalan hangs on a wall.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Abed Shehabi is a vigilante in the Serian neighbourhood, which borders Sheikh Maqsood. ‘If thieves flee into the SDF area, we or the Aleppo police cannot pursue them’, he complains. Mohammad Khalil, chief of the Kurdish police in Sheikh Maqsood, agrees. ‘We cannot cooperate directly with the Aleppo police. As long as the constitution does not accommodate groups other than Arab Sunnis, Syria will remain a country full of separate pieces that do not work together.’

The war has divided Aleppo not only physically, but also in less visible ways. Bohar’s friend Fahima is a lawyer. ‘The Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria cannot issue official documents’, she says. ‘For example, for a client who wants family reunification with his wife in Belgium, I have to collect those documents from the town hall in Aleppo.’

But on 1 April, the Sheikh Maqsood self-government and the Al-Sharaa government reached a temporary agreement. The military SDF withdrew, but the Autonomous Administration and Khalil’s police force were allowed to remain. They are now working with the Aleppo government, and the sandbags and checkpoints have disappeared. It could be a test case for lifting the border between all of NES and the rest of Syria.

Mohammad Khalil, chief of the Kurdish police in Sheikh Maqsood

© Emiel Petrovitch

Language revolution in north-east Syria

Northeast Syria has functioned as a breakaway state within the state for more than a decade, where Kurds, Assyrian Christians, and Arabs govern together. A hard border cuts across the country. Soldiers and passport booths are lined up in a desolate wasteland. The so-called manager of the border post – he wears no uniform – arrives on a motorbike to check our journalistic clearance.

Once inside the autonomous region, we meet Education Minister Samira Haj Ali (PYD, the party that founded the YPG militia in 2011) in her office in Qamishli, the capital of the autonomous region, a full 500 kilometres from the ‘border’.

‘The Assad regime tried to erase our language, but we stood firm’, she says defiantly. ‘Since declaring self-rule in 2014, our children have been learning to read and write Kurdish for the first time in Syrian history. We have evolved from secret language classes to 34,814 teachers, our own universities, and 3,679 schools, thanks to thousands of martyrs.’

Above: Samira Haj Ali, Minister of Education for autonomous Northeast Syria. Below: Children learn Kurdish at a primary school in Sheikh Maqsood, Aleppo.

© Emiel Petrovitch

‘Pioneers taught villagers the Kurdish alphabet underground’, says Ahmed Majid, a councillor for the PYD in Gerbawi village. At a cemetery for fallen YPG soldiers stands a large portrait of Öcalan. As the YPG captured more territory and self-government was declared, Kurdish schools appeared in the most remote villages, set up by local education committees. A new institute was established to train teachers and develop a curriculum in the three official languages: Kurdish, Arabic, and Aramaic.

More than one hundred thousand Kurdish pupils are following the new curriculum. Over six hundred thousand Arabic children, along with a small group of Assyrian Christian children, follow the same curriculum in their own language. But they also learn Kurdish. ‘Equality begins in the classroom’, says the minister.

‘The Language Institute started with seven, but now has 150 linguists’, says director Renas Hassan. He once studied business administration in Damascus, but left in 2011 when the conflict began. Back in Qamishli, he chose the new teacher training programme at the new Rojava University.

‘The education system reflects the linguistic and ethnic diversity of NES and is more advanced than that of the new Syrian government. It can be a model for Syria as a whole’, says Hassan. ‘Between 2015 and 2017, universities were even established in Afrin, Qamishli, and Kobane. They collaborate with the American University of Arizona. Academics can access the Americans’ online library for research.’

Turkey is an obstacle

In Afrin, the university and all educational institutions disappeared after the 2018 Turkish invasion. Pro-Turkish mercenaries from the so-called Syrian National Army (SNA) drove out the PYD, after which Turkey introduced a Turkish curriculum.

‘We took tens of thousands of refugee students from Afrin into our schools’, says Roshin Yousef, headmistress of a school in Sheikh Maqsood. In the playground, refugee children take gymnastics lessons. Ages vary widely in the classrooms because many children have missed years of schooling due to displacement. Classrooms have been converted into dormitories, with mattresses instead of desks, and kitchens.

Along with the students came teachers from Afrin, including Yousef. Although there is still a shortage, says Akid Hannan, co-chairman of the education committee in Sheikh Maqsood. And what if these children ever return to Afrin? Will they find their familiar curriculum there again? ‘We want to rebuild our schools and government institutions in Afrin’, says Hannan. ‘Negotiations are ongoing, but Turkey is the biggest obstacle.’

Families fleeing Turkish attacks in Afrin have found shelter in schools in northeast Syria. Classrooms have been converted into dormitories.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Kinderen spelen tussen schoolbanken die uit de klaslokalen werden verwijderd.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Blurring border

Until 2018, Afrin was still part of NES. Mohamed Hossein, Bohar’s father, still lives there. He is waiting for us near Sheikh Maqsood in Aleppo, as his Afrin number plate does not allow him to enter the district himself. ‘We don’t take risks, because Turkish intelligence sometimes tries to smuggle in car bombs’, Nouri Sheikho had already explained to us. Sheikho is the de facto mayor of Sheikh Maqsood. He helped negotiate the reintegration of the district into Aleppo.

We take a taxi and meet Mohamed just outside the district. Agreeing on a precise meeting place was necessary. Bohar cannot call her father because people from Afrin are required to use the Turkish network.

The road between Aleppo and Afrin is no longer closed, but the area remains behind an invisible border. At the first checkpoint of the pro-Turkish mercenaries, a masked soldier stops us sullenly. Mohamed is nervous. These mercenaries have looted thousands of Kurdish homes. But as soon as we show our permission from Damascus, the soldier removes his mask and suddenly becomes overly friendly.

A checkpoint of the pro-Turkish mercenaries occupying the Kurdish region of Afrin.

© Emiel Petrovitch

As we drive into Afrin, it feels as if we have entered Turkey. Turkish flags fly everywhere, military checkpoints dominate the streets, and people use the Turkish lira. On 9 April, there was a glimmer of hope: the Turkish-backed SNA would withdraw from Afrin, and Syrian police would regain control.

During the Newroz festival on 21 March, we already saw some Syrian officers in the city, but several residents say that the Turkish-backed mercenaries remained and simply changed into different uniforms. Afrin appears to be reintegrated into Syria, but appearances can be deceptive.

‘Choosing between the pro-Turkish mercenaries and the Syrian police, led by ex-jihadist Al-Sharaa, is like choosing between plague and cholera. But for us, the choice is clear: we want to belong to Syria, not to criminal Turkey’, says NGO worker Imad Hossein.

This year, the Kurdish New Year festival was allowed again, after being banned last year under Turkish occupation. The revival of cultural traditions points to a blurring of boundaries between communities.

During Newroz in Afrin, a long-bearded Syrian policeman asked our photographer to take his picture. He proudly posed with the Kurdish and the new Syrian flag. Nouri Sheikho believes it sends a double message. ‘Beautiful, that’s what we want. But it’s also the image Al-Sharaa wants to show the world now, while there is still no inclusive constitution. Appearances are not enough.’

A Syrian police officer poses with the Kurdish flag during Newroz.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Syrian federalism

‘The three territories – Sheikh Maqsood in Aleppo, Afrin, and greater northeastern Syria – must become part of Syria again’, says Minister Haj Ali. ‘Our goal is for the new Syrian state to officially recognise our diplomas, institutes, curricula, and teachers-in-training. Our teachers should be able to teach in all schools and universities in Syria, not just in NES.’

For ten years, pupils and university students have been graduating with certificates that are not valid in the rest of the country. They can use them in NES, but that increases the risk of a segregated region. ‘We were always aware of the risk’, says Haj Ali, ‘but we created a fait accompli. That is the only reason we are now strong in the negotiations for a federal state. Everything exists. Only the official recognition is missing.’

In early April, that recognition seemed to be within reach. President Al-Sharaa appointed a Kurd from Afrin as the new education minister in Syria’s interim government. He negotiated with Haj Ali and UNICEF. Diplomas from educational institutions in NES would be officially recognised.

Thus, the contours of Syrian federalism are cautiously emerging. NES administrations are already trying to act like a federal state within Syria. The Kurdish name ‘Rojava’ was replaced with the neutral ‘Northeast Syria.’

And in a government building in Hasakah, Minister Shekhmus Ahmed gave an interesting answer to our question about whether we could photograph him in an office where a portrait of PKK leader Öcalan hangs. ‘Our government is linked to Syria, while Öcalan is just a Kurdish leader. The impression might be that we are separatists.’

Diversity in Northeast Syria's governance: the Minister of Social Affairs is a Kurd (left), the co-chair of Hasakah's governing council is an Assyrian Christian (right), her deputy an Arab Muslim (center).

© Emiel Petrovitch

But then why does the portrait hang there? ‘Because we are influenced by Öcalan’s philosophy of democratic confederalism. But that does not mean we are members of the PKK.’ Sitting next to him are the co-chair of Hasakah’s governing council and her deputy. One is an Assyrian Christian, the other an Arab Muslim. They are all part of the administration of Northeast Syria. They want to implement this kind of diversity in governance across Syria.

Hasakah is bathed in a red glow. Storm winds blow clouds of dust through the streets, mixed with the acrid diesel smoke from generators. In the home of parliament speaker Siham Quryo (Syriac Union, ruling party of the Assyrian Christians), the power goes out. A dim backup light flickers on. Among the 1970s furniture are an old radio, a bust of Lenin, and books by Russian communists.

Her family of Assyrian Christians was expelled from Mardin in present-day Turkey during the 1915 genocides. The family fled to Hasakah, which later became part of Syria. There, Quryo grew up in a politically engaged family of Syrian communists.

‘We support Öcalan’s democratic confederalism. It is the new model for the whole Middle East. And now I suppose you are going to say I belong to the PKK?’ says Quryo, with frustration and derision. ‘No way. We Assyrians are fighting alongside the Kurds against Arab jihadists and Turkey.’

According to Nouri Sheikho, Turkey wants a strong, centralised Syrian state with an Islamist constitution. ‘We categorically reject that. If they do not recognise our self-government, we will not recognise the Syrian government. We have made enough sacrifices to free ourselves from Arab dictatorships and religious fanatics. Without Turkey, we might be able to reach an agreement on federalism, but Turkey is oppressing both us and Al-Sharaa.’

Northeastern Syria is itself a federal state. Seven cantons each have their own government and parliament. There is one federal parliament, of which Quryo is the president. ‘It is a lie that we are separatists’, she says. ‘We are even willing to share the oil resources in NES fairly across Syria. And we can still adjust our social contract between Kurds, Assyrians, and Arabs.’

The system of governing councils and committees, from village to federal level, is based on Öcalan’s vision and replaced the Assad regime’s departing institutions. No elections have ever been held, because, according to Quryo, Turkey would attack them. Instead, consultations were held with representatives of all ethnic groups. That is how the social contract was created.

New Year celebration of the Assyrian Christians in Qamishli, Northeast Syria (NES).

© Emiel Petrovitch

Weapons under the table

‘Do you really believe that Syria is suddenly a normal country?’ asks a Kurdish arms dealer from Afrin. He armed the YPG in 2012 and still has many contacts within the arms smuggling business. ‘Several militias captured weapons from Assad’s army and are now selling them around Al-Bayda and Tadmur. We buy from them, but we know that ISIS also buys weapons there. So we are preparing for a new conflict.’

In his luxurious flat, overlooking Lake Assad and a refugee camp in Tabqa, there is a weapon in every room – to be ready for attacks. ‘We no longer trust Arabs’, he says after a series of push-ups in his personal gym. He calls the SDF’s withdrawal from Sheikh Maqsood ‘a facade.’

‘If Israel creates a passage from the Golan Heights to our territories, it can support us better’, he says. ‘Until our self-government is recognised in a federal Syria, Israel’s support remains our reserve option.’

Nouri Sheikho puts everything into a historical context: ‘We Kurds have lost 100 years since modern Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran were created. Now that there is a plan for a new Middle East, we are seizing our chance. We are not going to lose another hundred years. Our moment is now.’

In het appartement van een Koerdische wapenhandelaar staat in elke kamer een wapen. ‘Om klaar te zijn voor aanvallen. Wij vertrouwen geen Arabieren meer.’

© Emiel Petrovitch

This article was translated from Dutch by kompreno, which provides high-quality, distraction-free journalism in five languages. Partner of the European Press Prize, kompreno curates top stories from 30+ sources across 15 European countries. Join here to support independent journalism.

The translation is AI-assisted. The original article remains the final version. Despite our efforts to ensure accuracy, some nuances of the original text may not be fully reproduced.

If you are proMO*...

Most of our work is published in Dutch, as a proMO* you will receive mainly Dutch content. That said we are constantly working to improve our translated work. You are always welcome to support us both as a proMO* or by supporting us with a donation. Want to know more? Contact us at promo@mo.be.

You help us grow and ensure that we can spread all our stories for free. You receive MO*Magazine and extra editions four times a year.

You are welcome at our events free of charge and have a chance to win free tickets for concerts, films, festivals and exhibitions.

You can enter into a dialogue with our journalists via a separate Facebook group.

Every month you receive a newsletter with a look behind the scenes.

You follow the authors and topics that interest you and you can keep the best articles for later.

Per month

€4,60

Pay monthly through domiciliation.

Meest gekozen

Per year

€60

Pay annually through domiciliation.

For a year

€65

Pay for one year.

Are you already proMO*

Then log in here