Rebuilding Syria: Is there life after the apocalypse?

One year after Assad’s fall, returning Syrians are living amid the ruins

© Emiel Petrovitch

© Emiel Petrovitch

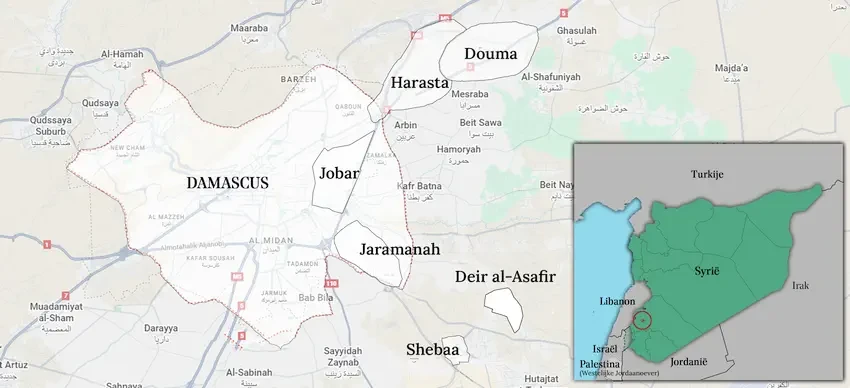

In Damascus province, Assad’s and Russia’s bombings wiped entire cities off the map. Rebuilding them will cost ten times Syria’s GDP, yet international support remains largely absent. MO* spoke with returning residents and local organizations defending their rights.

Mohamed Telawi leans against the wreck of a burned-out car, next to the small office of his auto repair shop. Shiny new floor tiles stand in stark contrast to the surrounding devastation. “I’m 78,” he says. “I’ve lived through many wars, but the hell between 2012 and 2018 was unlike anything else.”

In Harasta, a town east of Damascus that was completely flattened by bombings, returning residents are trying to survive amid the rubble. Some have cautiously begun renovating their apartments in collapsed buildings.

The return of displaced people has heightened the demand for basic services and created new challenges: residents are already making substantial personal investments, even though these uninhabitable buildings will eventually be demolished once Syria’s large-scale reconstruction begins.

That reconstruction can only truly start once all economic sanctions against Syria are lifted. The EU did so on May 28, 2025, followed by the United States about a month later. However, full implementation is still pending.

During a historic visit to the United States on November 10, 2025, Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa emphasized his central message: “Syria’s stability affects the entire region. Stability is closely linked to economic development, which depends on the lifting of sanctions. These discussions have been ongoing for months, and we are still waiting for the final decision.”

Lack of Investment

For years, the towns and villages in the Rif Dimashq province were centers of protest and armed resistance against former president Bashar al-Assad. Many residents of Harasta, Deir al-Asafir, Douma, and Jobar joined the rebels, or later, Islamist groups.

Between 2012 and 2018, the area was besieged and starved by the Assad regime and its ally Russia. In 2018, entire cities and villages were wiped off the map. Only a few people were able to stay or return to their destroyed homes.

Six years later, after Assad’s fall, a small number of residents returned. They are now trying, brick by brick, to rebuild their old lives.

But the challenges are enormous. One-third of Syria’s total capital stock—all infrastructure and physical assets in the country—has been destroyed or damaged. The World Bank estimates the total reconstruction costs at $140–$345 billion—ten times Syria’s entire GDP. Without international support, large parts of Syria will remain in ruins. Investments to date have been far from sufficient.

In September, the new Syrian government launched the Syrian Development Fund (SYDF) and the Supreme Council for Economic Development, aiming to attract domestic and foreign investment. In October, they received delegations from the German development agency GIZ, the UNDP, and representatives from Turkey.

A father with his child in Harasta.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Harasta

Syrians driving from the capital to the eastern towns witness the landscape shift from bustling city life to an apocalyptic wasteland.

“Two cousins are still somewhere under the rubble,” says Mohamed Telawi. “My wife’s brother was shot dead before my eyes. During the siege in 2015, someone sold his car for a single bag of rice. In 2018, we fled. When we returned, Assad’s soldiers had destroyed and looted everything. Restoring this little office cost 40 million Syrian pounds (about €3,000). President Al-Sharaa gives us hope. We no longer live under Assad, and my children can visit me. But without foreign aid, we won’t make it.”

In September, UNICEF began restoring Harasta’s water network with funding from South Korea, aiming to provide safe drinking water again. In October, the municipal council submitted a new zoning plan for the city center to the Rif Dimashq provincial authorities. Since then, residents are no longer allowed to carry out renovations themselves. The new plan calls for a complete overhaul of the area.

But what about the personal investments that Khaled Ibrahim Rhail and Fatme Omar have already made in their heavily damaged apartment? “We returned in 2018,” says Rhail. “Just fixing this staircase took a month. We live in a ruin, but step by step, we restored the façade and the kitchen, paying for everything ourselves. The Assad regime even imposed extra taxes on building materials and demanded bribes for rebuilding what they had destroyed. And now the new government wants to take that away from us too?”

Khaled Ibrahim Rhail with his granddaughter in Harasta. On the left is their apartment, which they were renovating. On the right is a destroyed and empty apartment.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Bashir Kharnoub in Harasta.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Through Rhail’s window, all that can be seen is a sea of rubble. His daughter sits quietly in a corner. She was once hit by a bullet, which damaged her ribs and kidneys. Her husband was arrested and disappeared into the notorious Sednaya prison.

Bashir Kharnoub spent seven years in detention. When he returned to Harasta, he found his top-floor apartment completely wiped out. An unexploded rocket still juts out of the concrete. In a corner of the ruin, he placed a chair and a toilet. Kharnoub survived years of siege and starvation in Syria, but lost his family at sea in Europe. “My daughter, her husband, and their three children drowned on the way to Europe,” he says, his face betraying no emotion.

On a mound of rubble, a few young men sit smoking. A man rides past on a motorcycle, holding his young son tightly. Ismaiel Al-Arbene, who has lived in Istanbul for ten years, has returned to Harasta to find his old home.

“I don’t even recognize the streets anymore,” he says. “Returning isn’t so simple. My son Bilal was six months old when we fled. He missed years of schooling but eventually learned Turkish. If we returned to Harasta, he would fall behind again. I’m trying to teach him Arabic by hand myself. Electricity? Sometimes only one hour a day. Solar panels? Only for the municipal building. In Douma, it’s a bit better.”

Ismaiel Al-Arbene with his son in Harasta.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Douma

Along Douma’s wide avenues, solar panels line rows of streetlights. A few apartment buildings with restored façades, funded by wealthy families, stand as isolated blocks amid a sea of ruins. Douma benefited from its secular intellectuals and vibrant civil society during the “liberation” of 2012 and after Assad’s fall in 2024.

But internal struggles were constant. At the start of the uprising, the Assad regime released radical Islamists from prison to sow fear, and began arresting intellectuals. Snipers fired indiscriminately at civilians, who in turn armed themselves to protect demonstrators.

In June 2012, massive bombardments began. Islamist groups emerged, but a group of citizens continued to pursue secular governance. Amin Badran, a civil engineer, established a council when the Assad regime withdrew from the area in 2012.

“It took months to form a non-ideological council of technocrats,” Badran recalls. “French NGOs supported the council, but Islamists created a parallel administration. Debates were especially intense in education: we thought it was enough to remove Assad propaganda from schoolbooks, while the Islamists wanted to implement a strictly religious Saudi curriculum.”

Although many Douma residents fled, Assad could not completely destroy civil society. “I stayed, despite the siege and my children’s ongoing health problems from hunger,” says Badran. “On December 8, 2024, it felt like our sacrifices had not been in vain.”

Badran’s efforts show that alongside physical reconstruction, restoring social fabric is crucial: trust, good governance, community structures, and cooperation between administrative levels. Today, Badran’s council is part of the municipal government, attracting donations for schools, electricity, solar panels, security cameras, and street renovations.

“We asked Douma businesspeople in Turkey and Egypt for support,” says Badran. “For example, we restored the 1936 courthouse, which Assad’s retreating troops had set on fire. We also pay teachers’ salaries.”

The Turkish government supports Douma’s school renovations through its development program.

Syrian-Belgian university researcher Yahia Hakoum speaks with Amin Badran in Douma. In the background are the solar panels installed thanks to Badran's local council.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Deir al-Asafir

Harasta and Douma are cities, but villages were also wiped off the map. In a holiday home at “Happy Land,” a deserted post-apocalyptic amusement park near the village of Shebaa, ten men gather over coffee and breakfast. Others still lie sleeping on mattresses. When Assad’s army retook Shebaa, Deir al-Asafir, and other villages in 2018, they were forcibly relocated north.

Barely hours after Assad fled on December 8, 2024, they had returned to Deir al-Asafir. Their homes were completely destroyed. The vacant holiday cabins now provide temporary shelter.

The day drags on. Armed men, former rebels now working with the new Ministry of Defense, visit the cabin. They smoke hookahs and greet Dr. Ayman Issa. “During the siege, I was the only doctor in the area,” Issa says. “We set up a field hospital in the basement of a construction site. I treated wounded from across East Damascus every day, including victims of the 2014 chemical attack.”

On February 26, 2016, Russian planes bombed the field hospital. “Thirty-six people died that day,” Issa recalls. Today, the hospital is empty, looted, destroyed, and dusty. Medicines still lie scattered among the rubble.

The local school was also bombed that day. Mohammed Akkar looks at the last lessons written on the blackboard. Akkar helped found the local revolutionary council in Deir al-Asafir. “Ordinary residents, shopkeepers, dentists, farmers, teachers, became administrators. Between 2012 and 2018, we served 63 villages and towns with humanitarian aid, orphan care, food distribution, everything.”

Left: Mohammed Akkar looks at the site where a Russian missile struck the Deir al-Asafir school. Right: Akkar shows the side of the school that has already been rebuilt (the right side in the photo).

In 2018, these local administrators were branded “terrorists” by Assad and Russia and forcibly relocated north. Those left behind, like Husain Guzail, were arrested. Guzail had coordinated humanitarian aid for the local council.

In the alley in front of his house, he demonstrates the torture he endured: hours standing under the scorching sun, bound in car tires, hung with arms tied behind his back, nails pulled out, beaten with sticks, electroshocked.

“We’ve seen so much,” he says. “We even ate grass. Nights we went to sleep hungry. And then a judge accused me of smuggling money for terrorists, the children we helped were ‘children of terrorists.’ I was tortured in prison for three years.”

Despite everything, Guzail continues to hope that Syria can be rebuilt. “But this rubble that will be cleared, these are also our memories. Ah, the most important thing now is that the dictator is gone.”

After Assad’s fall, Mohammed Akkar and others immediately began stabilization efforts: removing collaborators, preventing looting, settling personal conflicts, and establishing new committees.

Reviving agriculture is a top priority. Deir al-Asafir lies amid vast farmland and olive groves dating back to Roman times. Assad’s soldiers cut down thousands of trees. The water treatment plant was destroyed, and drought now threatens crops. Without diesel, irrigation pumps remain idle.

Akkar is now seeking project support from French NGOs. “We want to work in an environmentally sustainable way and invest in solar panels, but our resources are limited. In the north, there’s electricity 24 hours a day; here, not yet. Our goal is to make the countryside flourish again. Without a healthy countryside, even rebuilt cities cannot be livable.”

Husain Guzail shows how he was tortured.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Mohammed Akkar in one of the ancient olive groves of Deir al-Asafir.

© Emiel Petrovitch

Jobar

Narrow rural roads wind between fields and rubble toward Jobar, the first district of the capital after the eastern countryside. Jobar is notable because it was controlled by rebels for years, bringing them to within barely two kilometers of Damascus’s Old City. The result: Assad and Russia wiped all of Jobar off the map.

The apocalypse here is even more breathtaking. The once vibrant district, home to 400,000 residents, bustling markets, and even one of Damascus’s oldest synagogues, has now vanished.

Jobar’s local council organizes an iftar among the rubble, for the mothers of fallen rebels. Tables are arranged in a row between collapsed buildings. Songs for Allah and the rebels blare from speakers. Mothers step forward one by one to receive an emblem of honor. “This is finally recognition that we are mothers of freedom fighters, not mothers of terrorists,” says one of them.

But hosting the iftar has a deeper purpose. “We are reviving what is dead,” says a council member. “We refuse to accept Jobar’s disappearance. We want our district to be visible so the world understands that support is needed. Our memories are in every stone. We have the official population registers and land cadastre. We demand that the province take this into account in the reconstruction process.”

Jobar, a Damascus neighborhood, was completely bombed by Assad's army and Russia during the uprising. A local self-government organized a fasting meal amid the rubble to honor the mothers of fallen fighters. | Video: © Emiel Petrovitch | Video: © Emiel Petrovitch

Rebuilding Syria is likely to create tensions between the regional authorities' new zoning plans and residents’ desire to retain or reclaim their property. In Jobar, these tensions are already unfolding: the local council has proposed its own zoning plan as an alternative to the provincial one and employs its own lawyers to monitor every step.

Reconstruction can be as destructive as demolition, it can erase identity and history. The new government under President Al-Sharaa, along with international donors, faces a delicate balancing act. Their decisions will determine whether they gain new allies or make new enemies of a population that has already suffered for far too long.

‘Bombed flat’

© Emiel Petrovitch

This article was originally published in dutch on december 8th.

Translation by Pieter Stockmans

More on Syria

If you are proMO*...

Most of our work is published in Dutch, as a proMO* you will receive mainly Dutch content. That said we are constantly working to improve our translated work. You are always welcome to support us both as a proMO* or by supporting us with a donation. Want to know more? Contact us at promo@mo.be.

You help us grow and ensure that we can spread all our stories for free. You receive MO*Magazine and extra editions four times a year.

You are welcome at our events free of charge and have a chance to win free tickets for concerts, films, festivals and exhibitions.

You can enter into a dialogue with our journalists via a separate Facebook group.

Every month you receive a newsletter with a look behind the scenes.

You follow the authors and topics that interest you and you can keep the best articles for later.

Per month

€4,60

Pay monthly through domiciliation.

Meest gekozen

Per year

€60

Pay annually through domiciliation.

For a year

€65

Pay for one year.

Are you already proMO*

Then log in here